Most Hoquiam Post Office patrons are unaware that the second floor of the historic building houses a treasure. Here Barbara Bennett Parsons lovingly takes care of the extensive legacy of her father, the late Hoquiam artist Elton Bennett (1910-1974).

![]() Most of Elton Bennett’s work consists of serigraphs also called silk-screens. The artist loved this print making technique because it allowed for great flexibility and finesse. A unique image would evolve with each individual pulling from a basic screen.

Most of Elton Bennett’s work consists of serigraphs also called silk-screens. The artist loved this print making technique because it allowed for great flexibility and finesse. A unique image would evolve with each individual pulling from a basic screen.

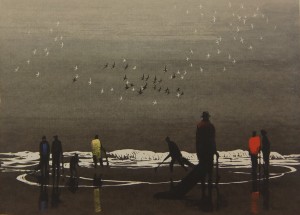

Vast foggy seascapes and looming mountain sides, mysterious forests with multilayered vegetation worked out in elegant precision show the sublime beauty of the Pacific Northwest coast. Majestic tall ships navigate wild waters or appear shrouded in layers of mist. The immense landscapes are inhabited by smatterings of wonderfully expressive human figures whose backs are turned to the artist as he is recording their activities.

“I watched Dad work,” remembers Barbara. “I watched his fluid hand motions. Artists have this special essence. I saw his soul.”

A prophet is never accepted in his hometown. This is certainly true for Elton Bennett. Although the 5,041 pieces Barbara and her sister Evelyn inherited depict half a century of Grays Harbor history, they are most appreciated outside the Harbor as far as Australia, Germany, Scotland and even Turkmenistan.

Elton Bennett was a simple man who grew up in a poor family. “My father always wanted to be an artist,” Barbara relates. “He started drawing as soon as he could hold a crayon but my grandfather did not support him.” When young Elton attended Washington State University at age 17, his father opposed his son’s taking art classes even though the young man was paying for tuition with his own hard-earned money.

After only one year of college, the Great Depression hit. Bennett had to return home and work to support the family. He took any job opportunity that presented itself drawing his surroundings whenever time allowed. A pile of caricatures of his mates were found stashed away in a drawer on a dredge he had worked for the Port of Grays Harbor.

When World War II began, Bennett joined a Navy Construction Battalion which took him to the Aleutians and to Pago Pago in American Samoa. He kept drawing – on colored construction paper!

Back home in Grays Harbor, Bennett met his wife Flora on an outing with the Olympics Hiking Club which, according to Barbara, functioned as a singles club at the time. Flora, a woman of strong character, encouraged her husband to pursue his dream of becoming an artist. Investing his GI Bill money in his art education, Bennett embarked on a miserable two years study at the Portland Museum Art School, where neither his style nor his personality were appreciated.

Back on the Harbor, two daughters were born to the Bennetts. In 1956, after three years of hard work, scrimping and saving to accumulate a financial nest egg, Elton Bennett finally felt confident enough to hang out his shingle as a full-time artist. “He never ceased to be grateful to be able to support his family doing what he loved,” Barbara remembers. “We all went to shows together in summer. Dad always took his family with him when he travelled.”

Bennett soon established himself as an artist. Eventually he was able to add an A-frame art studio to the family home overlooking the Elton Bennett Trail, the Hoquiam hillside named in his honor. An ever increasing number of visitors came to the house. “Evelyn and I became receptionists. We gave tours so that Dad did not need to interrupt his work,” Barbara relates. “Invariably, Mom made the guests stay for dinner.”

Elton Bennett’s personality lacked the artistic ego. Barbara describes her father as a ‘gentle’ man in the literal sense of the word. He strongly opposed the art scene with its airs of exclusiveness. With silk screening as his medium, he could include the common man into his art world. Creating up to 100 serigraphs from one screen allowed him to make a good living while keeping his work accessible to low income art lovers. He never sold a serigraph for more than $15.

Continuing in the spirit of her father, Barbara has donated much of his art to Grays Harbor public spaces. She has been releasing a few pieces into the community every year. Her goal is to seep her father’s work into people’s consciousness as they find themselves surrounded by its beauty. This year, the Shelton School District will benefit from 20 original pieces by Elton Bennett.

Barbara plans to bequeath the pieces left after her death to the Polson Museum. Grays Harbor non-profits may approach Barbara for original art work for fund raising auctions. “I want the community to be recipients of Elton Bennett’s legacy,” she says with a smile.

An Elton Bennett Art Tour could include the Hoquiam and Aberdeen City Halls, Timberland Libraries of Hoquiam, Aberdeen, Montesano and Westport, Westport Maritime Museum, Polson Museum, Museum of the North Beach, Chehalis Valley Historical Society Museum, Hoquiam High School, Aberdeen High School and the Taholah School District.

Contact Barbara at 360-532-3235 or barbarapar@comcast.net. Visit EltonBennett.com to shop for original Elton Bennett serigraphs, reproductions, note cards, magnets and more.